Born in the segregated South, Anderson was determined to become a doctor at a time when many African-Americans had limited access to basic health care.

Never quit: Denied admission to numerous medical schools, he served as a hospital corpsman during World War II, learned mortuary science and enrolled at Des Moines Still College of Osteopathy and Surgery (now DMU).

Never quit: Refusing to back down Anderson and his wife, Norma, became early leaders in the civil rights movement along with their friend Martin Luther King Jr.

Never quit: At a time when even white D.O.s faced professional discrimination, Anderson rose to the top, advocating for his profession and other African-American physicians.

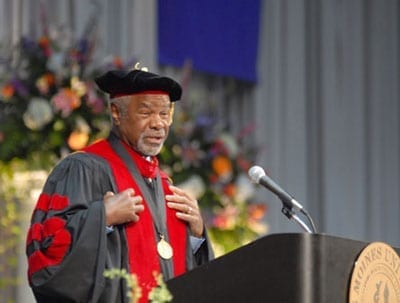

Anderson’s life embodies another theme of his May commencement address to DMU graduates: Take what life hands you and make the most of it.

Anderson’s hard work and fearless leadership broke barriers in his profession and across society. That’s why DMU honored him as a Pioneer in Osteopathic Medicine and Public Service this year.

“I’ve had many doors closed in my face, so I found ways to make other doors open,” says Anderson, now vice president for academic affairs in osteopathic medical education at Sinai-Grace Hospital in Detroit. “Nothing is impossible if you don’t give up on your dreams.”

Fighting for civil rights

Anderson established his first practice in Albany, Ga., upstairs from a pool hall and liquor store.

“Almost from the first day I had an office full of patients–on some days as many as one hundred,” he recalled in the book he and Norma co-wrote, Autobiographies of a Black Couple of the Greatest Generation. He also made house calls, including to homes without electricity, indoor plumbing or heat. On occasion he delivered babies by driving his car up to a house’s window with its headlights on to allow him to see.

He and Norma also began forming an organization to end segregation in the city. At the group’s first meeting on Nov. 17, 1961, those gathered named themselves the Albany Movement and then elected Anderson its first president. Less than a month later, when hundreds of peaceful demonstrators–including both Andersons–were being arrested, the couple convinced Norma’s childhood neighbor, Dr. King, and his co-founder of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, Ralph David Abernathy, to come to Albany. Hundreds of people from across southwest Georgia flocked to the city to see and march with the civil rights leaders.

The movement continued in 1962 with organized boycotts of city buses and downtown stores. In January, Anderson, King and Abernathy were in jail again after a demonstration, on a day when King was scheduled to be on the NBC TV program “Meet the Press.” He wanted to remain in jail, but Police Chief Laurie Pritchett wanted to avoid drawing even more negative publicity upon the city. So the three jailed men drew straws, and Anderson went to New York City to appear on the program.

When program panelist James Kilpatrick, then editor of the Richmond (Va.) News Leader and a once-fervent segregationist, accused Anderson and King of inviting arrest “as a matter of showmanship,” Anderson retorted, “If exercising a constitutionally guaranteed right is inviting arrest, yes, we invited arrest.”

Anderson wrote that the Albany Movement was important because of how it changed perceptions: African-Americans “discovered that they had the power to effect change and could do it nonviolently,” and whites “came to the realization that Blacks were not happy and content with things as they were and were not going to accept it anymore.”

The movement also influenced subsequent civil rights movements throughout the United States. In the forward of Autobiographies, fellow civil rights leader Rev. Wyatt Tee Walker stated, “William and Norma Anderson were the heart and breadth of the Albany Movement. It was the Albany Movement that laid the foundation of the historic Birmingham campaign. It was in Albany that the movement developed the skills to mobilize an entire city for an assault on segregation and injustices.”

A professional pioneer, too

In 1963, Anderson decided to renew his studies to become a surgeon. DMU classmate and Detroit physician Charles Murphy, D.O.’57, helped him get accepted as house physician at the city’s Art Centre hospital. Anderson eventually got a surgical residency there, becoming the first black person to receive such an appointment at any Detroit hospital. He went on to become the hospital’s first black chief of staff and chairman of the board of the hospital corporation.

Anderson also was the first African-American certified by the American College of Osteopathic Surgeons and the first to serve as president of the American Osteopathic Association. In 1973 he became the first black person to serve on the DMU Board of Trustees. “You have assumed the role of leaders by earning your degrees,” Anderson reminded DMU graduates at commencement. “You have inherited the earth. What will you do with that inheritance?”