Perhaps I shouldn’t have read The Brothers Karamazov in the spring of academia. “All are responsible for all.” I underlined the words. I wanted to become those words. No one minds an impostor if they are helpful, if they are serving others. I found many charitable, worthwhile excuses for why I had more important things to do than drive three hours home to visit my family, depressed and dysfunctional, early in the season of Mom’s diagnosis of breast cancer. I didn’t know how to fix it. Instead, I sat lethargic on the college dormitory bunk and wept upon a greeting card Mom had sent telling me not to worry. Better to sit useless here, I thought, than to go home and stand by, useless, watching her suffer.

So I watched strangers suffer in homeless clinics and I held their hands and passed out pairs of socks and condoms, playing the part of a servant, trying not to feel like a traitor. I kept the pace over the next two years, racing away from pain rather than toward a finish line. With an avid sort of madness, I auditioned for parts in the dramas of others and ignored the crucial role I had been born into. I probably wouldn’t have gotten into medical school had I not been so hyperactive in my avoidance of feeling the Sadness.

Upon graduation, Mom had recovered considerably, and with one less breast and a head of stubble she showed up at my commencement. Everything was different. There was a new normal that we all were adjusting to fit into. Illness could threaten to rob us again, at any time. I think we all expected it to haunt us again soon, just like you might think after a winning gamble that you might have another good hand soon. We felt vulnerable. But the new normal had also shifted the epicenter of our family a safe distance from me. My brother and father were the shoulders that held Mom up while I offered an occasional phone call. And so I went on to Teach for America, to be responsible for All other than Mine, thinking that my absence from home during those tough times went unnoticed…

Who honestly feels at home in the care of others? The medically fluent doctors with formularies of savvy chemical cocktails shuffled their feet like teenagers at a school dance when consulting illness in the flesh…I’m shocked to see so many steel over when soggy, emotional gravity threatens to soil their white coats. It must come with longevity. Survival, maybe. Their walls are high and thick. Raw and self-afflicted with responsibility, I still feel everything…I never want to fail to listen or neglect to reach out and hold a desperate hand in silence. And for Mom, I should have gone home when I had the chance.

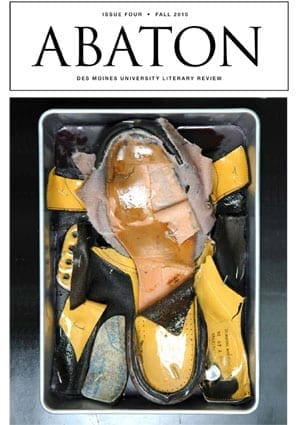

These days I wear my responsibility like a costume I can’t get out of at the end of the show. It’s the weight that only I seem to see in the mirror. The more I allow it to layer, the less I recognize myself… What courage, to simply be the character that you are. [My mother’s] noble discipline not just to know thyself, but to love thyself, bald or curly, helpful or useless, bemoaned or applauded, is the Finest Art. And since we spend more time living our scripts than reading them, often blind to consequence, still ahead of the finale, we must continue to show up and go on, impostors or not, giving all we have to stay present with each other in the moment with a certain grooviness and grace.