This is the first in a series of articles addressing the critical issue of medical care delivery capacity and utilization in the United States. Richard Belloff is an assistant professor in DMU’s master of health care administration program and a former managed care company CEO.

The premise: We have too much; we use too much!

The premise: We have too much; we use too much!

Health care reform in the United States is a topic that will not go away. Indeed, rather than putting the issue to rest, the passage of the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (PPACA) appears to have simply moved the matter out of the hands of lawmakers and into the arms of the courts. As of this writing, most expect the legality of all or part of the act to be resolved by the Supreme Court. However the Court rules, few expect health care reform to quietly fade into the background.

PPACA’s overarching goal is to expand access to health insurance for most Americans. The law’s principle focus is on health insurance reform, attempting to make it easier for consumers to obtain and retain health insurance. In many cases,the law will provide federal subsidies to help pay for this expanded coverage.

Further, the law seeks to encourage medical providers to become more “efficient” by promoting such concepts as medical home, accountable care organizations and expanded health promotion. One assumes that this drive for efficiency is to help make health insurance more affordable, by reducing, on average, the amount of medical services consumed by the average consumer.

In short, the law sets the ambitious goal of expanding insurance coverage for the many, while restraining overall utilization of medical services, the cost of that care, or both. As one can imagine, this is easier said than done.

However well intended, this focus on expanding coverage and reducing utilization and costs is predicated on certain assumptions about U.S. medical care that are not well founded. The first is that Americans utilize medical services at a level that is, put simply, wasteful. Clearly, “everyone knows” we Americans spend more money on health care than any other country in the world, and yet we do not compare favorably to other countries on such indicators as infant mortality and life expectancy. The assumption here is that these facts indicate a degree of waste that can no longer be tolerated.

The second assumption follows from the first. As more Americans obtain insurance and seek access to more medical services, existing care providers have the extra capacity or resources to deliver these services upon demand. In this instance, the capacity I refer to are the quantity of practicing physicians and the number of licensed inpatient hospital beds.

Again, this assumption of resource availability seems reasonable. “Everyone knows” we lead the world in hospital resources, medical technology and the number and quality of our physicians. We have the best medical schools and world-famous hospitals, so where is the problem?

The problem is that these assumptions may not be valid. As an economist, I was taught to always ask the question, “As compared to what?” So I recently went off in search of data that might help us determine if these assumptions are valid or more like wishful thinking.

The data: America’s resource profile and utilization rates suggest we may already be rationing medical care

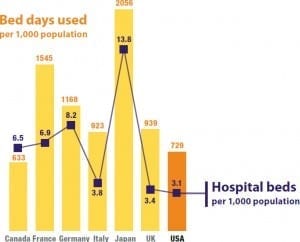

With regard to medical resource availability, the U.S. looks quite modest in several key areas. Consider that we have the fewest licensed hospital beds of the seven developed countries, and we are considerably below the median data for all OECD reporting countries.

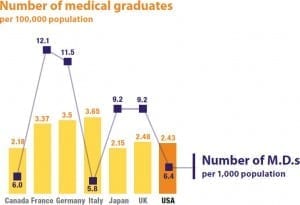

Similarly, U.S. physician availability is quite low as compared to our industrialized peers. France, Germany and Italy all have significantly more physicians per 1,000. Here again, the U.S. falls well below the median data for all OECD reporting countries.

Annual U.S. medical school graduate output is also quite modest, failing to keep pace with France, Germany, Japan and the UK. Again, we fall below the median for all reporting countries. This indicator may explain why the U.S. relies so heavily on the supply of international medical graduates, particularly for our primary care medical residency programs5,10. It appears that in the aggregate, U.S. medical schools lack the capacity to graduate sufficient numbers of physicians to keep pace with the rising demands of normal population growth and the increasing needs of an aging America.

Overall, what these data suggest is that the U.S. medical delivery system may not have sufficient resources to be able to accommodate increased demand from newly insured patients. In economic terms, we could consider certain aspects of the medical delivery system as “resource-constrained.”

From a cost perspective, these constraints are likely to create further problems. In general, when supply is not able to increase to accommodate increased demand, prices increase, not decrease. In this scenario, one would expect higher prices, longer wait times for services or both6.

Now, we turn to the law’s implicit assumption that U.S. patients consume too many medical services and that wasteful spending must be the result. Again, the comparative data do not appear to support this hypothesis.

In terms of utilization of hospital inpatient services, the U.S. exhibits very conservative usage of these expensive resources. Of the seven developed nations, only Canada uses hospital inpatient services at a rate lower than the U.S. In fact, length of stays for U.S. patients is the lowest of the seven industrialized nations and among the lowest of all OECD reporting countries. It appears that Americans are not eager to be hospitalized and, once admitted, quite anxious to leave, at least in comparative terms.

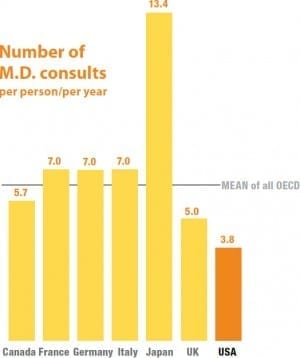

Similarly, U.S. patients tend to be most conservative in terms of seeing their physician. Here, the U.S. has the lowest physician consultation utilization among our seven-country cohort and is well below the median for all reporting OECD countries (3.8 annual visits per year versus the 6.3 median for all countries).

While not shown in our data, it is true that the U.S. does make use of more outpatient hospital services than many other OECD reporting countries. What is equally true is that as this shift from inpatient to outpatient care has occurred, total medical care costs have increased rather than decreased. This is thought to be largely a result of cost-shifting practices among U.S. hospitals1.

The next step: How did we get here, and where do we go now?

However surprising these comparative data are, they are far from conclusive. What does seem warranted is a closer look at our assumptions about the U.S. medical delivery system and about our citizens as consumers of health care. Working from faulty premises may have us addressing the wrong issues and trying to solve the wrong problems.

In our next installment, we will discover that the resource constraints that I refer to are not a recent development. In fact, some policy experts have been writing about this issue for some time2. The situation has been building for many years and, in some cases, are logical outcomes of deliberate policy decisions made over the course of decades9.

Moreover, there is recent evidence to suggest that medical resource constraints are escalating, resulting in such things as primary care physicians using emergency rooms to deal with patient volume that they cannot accommodate3, 11.

It seems that we may have arrived exactly where we have been headed.

References

- Accounting for the cost ofhealth care: a new look at whyAmericans spend more (2008).McKinsey Global Institute. LosAngeles, CA.

- Anderson, G.F.; Reinhardt,U.E.; Hussey, P.S.; Petrosyan,V. (2003). It’s the prices, stupid:Why the United States is sodifferent from other countries.Health Affairs, 22(3), 89-105.

- Emergency visits are increasing,new ACEP poll finds; manypatients referred by primary caredoctors (2011). PR Newswire U.S.

- Health care productivity(2006). McKinsey Global Institute.Los Angeles, CA.

- Koehn, Nerrissa, M.D.; FryerJr., George E., Ph.D.; Phillips,Robert L., M.D., M.P.H.; Miller,John B., M.D., M.P.H.; Green,Larry A., M.D. (2002). Theincrease in international medicalgraduates in family practiceresidency programs. FamilyMedicine, 4(6): 429-35.

- Mankiw, N.G. (2007).Principles of microeconomics (Fourth Ed.). Toronto, Ontario:Thompson.

- OECD frequently requestedhealth data (2010). Organizationfor Economic Cooperation andDevelopment. www.ecosante.org/oecd.htm.

- Reinhardt, U.E.; Hussey, P.S.;Anderson, G.F. (2004). U.S.health care spending in an internationalcontext. Health Affairs,23(3), 10-25.

- Sagness, Janelle (2007). Certificateof Need Laws: Analysis andRecommendations for the Commissionon Rationalizing NewJersey’s Health Care Resources.State of New Jersey.

- Sohi, Sajeet (2011). Internationalmedical graduates: apossible solution to the expectedphysician shortage. https://www.eyedrd/2011/05/internationalmedical-graduates-a-possiblesolution-to-the-expectedphysician-shortage.html.

- Tobler, L. (2010). A primaryproblem: More patientsunder federal health reform withfewer primary care doctors spelltrouble. State Legislatures, 36(10),20-24.

The premise: We have too much; we use too much!

The premise: We have too much; we use too much!