We are in a world of pain. From the prick of our first booster to the aches of arthritis, we experience pain at all ages in a variety of ways. Pain can range from irritating to excruciating, but it always serves a vital purpose. It alerts us that something is wrong and protects us from further harm by signaling the brain to take action. When the warning signal keeps transmitting, persistent pain can cause changes in the body and become a complex disease all its own.

The World Health Organization estimates that chronic pain affects as many as 100 million American adults, a number that is sure to rise. Chronic pain is associated with cancer, cardiovascular disease and obesity — prevalent diseases in an aging and overweight population.

With a third of its population in pain, the U.S. government has taken action to raise awareness of the epidemic. In 2000, Congress declared the aughts the Decade of Pain Control and Research. Ten years later, the Affordable Care Act required the Department of Health and Human Services and the Institute of Medicine to “increase the recognition of pain as a significant public health problem.” The increased emphasis has awakened the consciousness of the medical community and the general public, leading to a demand to ease our pain.

There’s a pill for that

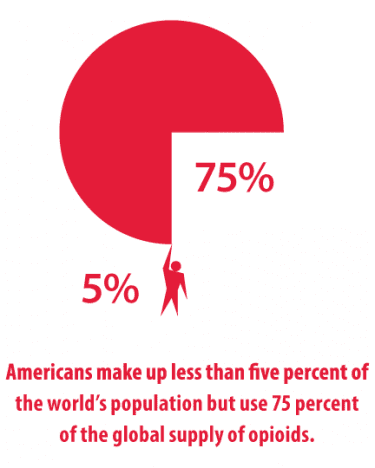

Despite the prevalence of pain, little has changed in its treatment. Opioids have been used to treat pain for centuries, dating back to 3400 B.C. when the Sumerians cultivated the poppy plant for medicinal purposes. Historically, the use of opioids was limited to treating only acute pain or cancer and end-of-life scenarios to make patients comfortable. Only recently have these painkillers been prescribed for chronic pain.

“In the ’90s, there was a big initiative strongly supported at the federal level to place more emphasis on pain,” says Edward “Pat” Finnerty, Ph.D., professor emeritus of physiology and pharmacology at Des Moines University. “The slogan was ‘Pain as the fifth vital sign.’ Pain is now perceived as something that can be controlled or managed — you can make it go away.”

This confluence of circumstances transformed the thinking in the medical community. Physicians began asking patients to rate their pain during office visits. Prescribing practices changed as opioids became widely accepted as a treatment for common chronic conditions like lower back pain, despite low-quality evidence to support their efficacy.

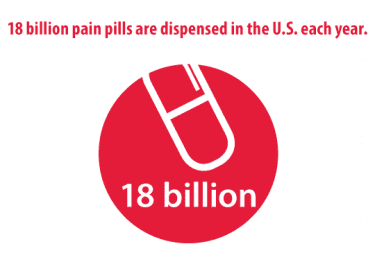

These more liberal prescribing practices were met with an insatiable appetite for painkillers. Opioid prescriptions increased 48 percent between 2000 and 2009. Last year, 230 million prescriptions were written for painkillers — enough to medicate every American adult for a month. As a result, overdose deaths involving prescription painkillers have quadrupled since 1999.

“It’s a problem we created. Society and government created this expectation. We’ve changed the behavior. Clinicians were more liberal with prescriptions,” Finnerty says.

“We live in a country where people want an easy, quick answer. They want to pop a pill in their mouth and do it again in four hours,” says Milton Klein, D.O.’77. “Higher doses of pain medications are not always associated with better outcomes. There hasn’t been any real proof that it makes a difference. It isn’t going to get a person better or find the underlying problem; it just covers it up.”

Breaking the habit

“There was a period of time where it was expected that when patients would come to the office, they would get medicines,” says Steven Quam, D.O.’78, a West Des Moines anesthesiolo- gist and DMU adjunct professor. “The pendulum has started to swing back the other way. I think doctors appreciate what’s going on and are trying to make the adjustment in their style of practice to address the pain needs without increasing the amount of pain meds they’re prescribing.”

Every person perceives, experiences and handles pain differently, so care must be tailored to the individual. A good treatment plan uses multiple modalities, including diagnostic testing, osteopathic manipulative treatments, physical therapy, behavioral health and spinal injections. Non-narcotic medications such as anti-inflammatories, muscle relaxants and anti-seizure medicines are also effective in relieving pain.

“These things all work together to provide a better package for our patients in trying to deal with chronic pain, and it really makes a big difference. Manipulation, I think, is a good modality for people who have the capability of doing that. I think they work well together. It’s a good skill to apply to patients,” says Quam.

Milton Klein uses a similar strategy at his outpatient physical medicine and rehabilitation and pain management practice in Coraopolis, PA. “I try to use a variety of techniques. The trend is less medication and more of other kinds of treatments that are sometimes considered ‘complementary.’ I think OMM fits right in with this.”

Klein is always looking for new methods to help his patients. He regularly uses electromyography to diagnose nerve and muscle problems and OMM and injections for pain relief. Seeing a need for non-pharmaceutical pain management, he added acupuncture to his practice a decade ago.

“People come to me and don’t want any pain meds. They say, ‘Doc, I want you to help me without having to take pills all the time.’ I wanted to do something that I hadn’t learned about in traditional training. It added another tool to the toolbox.”

The administrative and compliance aspects of prescription management are the most burdensome. Patients must sign medication agreements — and adhere to all guidelines — or face discharge for noncompliance. Urine tests, phone calls between appointments, patient education, intermittent pill counts and screens for substance abuse and mental health problems are all part of the standard of care in pain management practices.

“We have to see these patients on a frequent basis. You have to assess them more closely now. You can’t give them a long prescription because they need to be monitored,” says Quam. “The contract is important so the patient realizes that it’s important to use these medicines appropriately. That’s all part of our protocol.

“I’ve seen a lot of changes in pain over the 30 years that I’ve been involved with it. There will be ongoing changes as time goes forward,” he adds. “Using multiple modalities that work together, those will be the most appropriate things in trying to optimize the patient’s care.”

Trained for pain

Pain on the brain

There’s no doubt that chronic pain takes a physical toll on the body. Vanja Duric, Ph.D., is much more concerned with the effects persistent pain places on the mind. “What I’m interested in and what I’ve been working on since I was a student is how pain, especially chronic pain, makes you feel and affects your mood,” says the assistant professor of physiology and pharmacology.

“Why are chronic pain patients often depressed? What does pain actually do in the brain, especially brain areas that control emotions and feelings? That area of research has been kind of neglected.”

In over a decade of research, Duric has observed the linkage of depression and chronic pain. By looking at the markers in depression and exposing animals to different types of pain, he’s found similarities between the two. That’s particularly in the hippocampus, where there is a reduced production of new brain cells that leads to a loss of function. Antidepressants can reverse these negative effects for people with depression, but there are no comparable drugs to counteract the effects of long-term pain.

Duric is searching for a better approach to pain. Opioids were developed to relieve acute pain. The need for those drugs goes down as the body heals. In chronic pain, there is a disconnect in the pathophysiology, and the hurting never goes away. He hopes his current research project ultimately contributes to the development of new clinical strategies to prevent or diminish the mental health consequences of chronic pain.

“There’s still a lot to be learned about how pain affects the brain. Depression is present in roughly 30 to 50 percent of chronic pain patients. That’s a huge indicator that these emotional effects of chronic pain are something to be dealt with,” Duric says.

“We’re due for another pain treatment breakthrough. We’ve been using the same thing, the poppy plant, for 2,000 years. The only difference is now

we manufacture it. But we’re not just studying how we can reduce pain; we’re trying to study a certain component that’s underrepresented — that emotional component.”

“One of the hardest things to understand in the beginning is that chronic pain can’t be cured, only managed,” says Jennifer Kendall, D.O.’07. She learned that lesson early on in her physical medicine and rehabilitation training. As a resident at the University of Michigan, she became frustrated by her inability to cure a patient with chronic pain. The attending physician put it in perspective.

“He said, ‘Jenny, if you had a patient who was paralyzed, would you try to get them to walk?’” recalls Kendall, an interventional spine specialist at HealthEast Spine Center and medical director of HealthEast Optimum Rehab in Maplewood, MN. “You can’t change very much. You’re not going to fix chronic pain. Instead, we try to improve their function. They can become stronger and get back to what they’re doing.”

Specialists like Kendall are well trained to handle pain patients. But it’s primary care and internal medicine physicians and dentists, not specialists, who prescribe the bulk of painkillers. Primary care is the first stop in the health care system for pain patients, so more education in pain management is needed.

“Primary care physicians are doing the best they can, but they’re not pain specialists,” Kendall says. “Doctors that start people on pain medications may have had the best intentions. They give patients opiates because they don’t know what else to do. They feel they have to do something for their pain.”

A 2011 report from the Institute of Medicine found that pain received little attention in medical education, especially for primary care providers. It recommended an improved, standardized pain education curricula and assessment of pain knowledge on examinations for licensure and certification.

Des Moines University, like most of its peers, does not offer a specific course focused on pain. Instead, the topic is discussed throughout the curriculum as an inclusion in all clinical systems.

“What we do is typical. There’s an inclusion but not an overtly identified pain management course,” says Finnerty. “The idea of pain management isn’t a real priority for students until clinicals, but I think we do need more in our curriculum. We’re seeing more and more of this.”

While curriculum improvements may be necessary, osteopathic schools are better equipped than their allopathic counterparts to adapt to the changing philosophy on pain. Osteopathic manual medicine is a proven tool for pain management that carries few side effects, and it is embedded in every course for D.O. students. The osteopathic mindset is to look at other modalities first and take a more conservative approach when it comes to prescription drugs.

Kendall credits her osteopathic training for preparing her to treat pain. Observing and working with OMM physicians helped her understand the principles and gave her the confidence to apply them in clinical situations.

“Pain is so complex. It’s not always organic. You have to listen to the symptoms to make sure no other process is going on that contributes to their pain, making sure you are assessing pain in the whole person,” she says. “It takes a comprehensive approach, a team approach. Osteopathic medicine really lends itself to that. We treat the mind, body and spirit.”