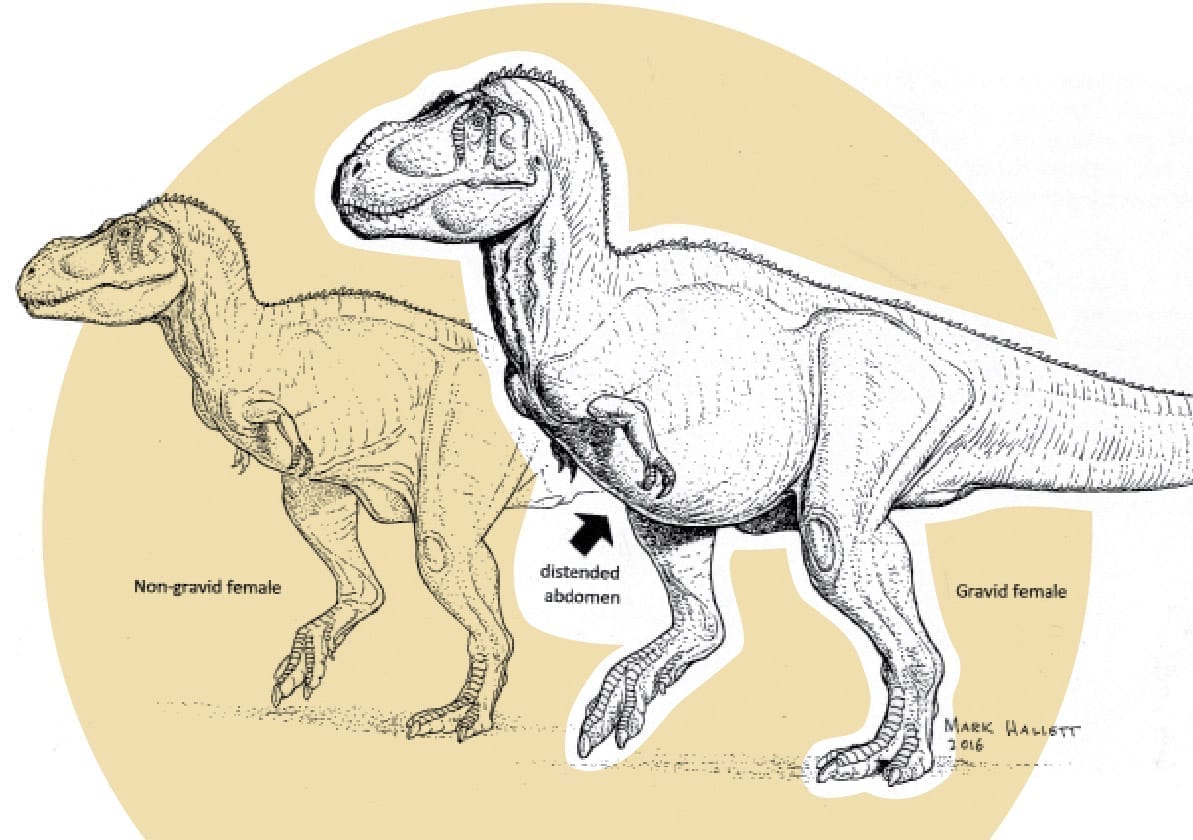

A pregnant Tyrannosaurus rex that roamed Montana 68 million years ago may be the key to discerning gender differences between theropod, or meat-eating, dinosaur species. Researchers from North Carolina State University, the North Carolina Museum of Natural Sciences and DMU have confirmed the presence of medullary bone – a gender-specific reproductive tissue – in a fossilized T. rex femur.

Beyond giving paleontologists a definitively female fossil to study, their findings could shed light on the evolution of egg-laying in modern birds. It also will spark new investigations of fossils and new applications of the researchers’ techniques.

“You might think all of the organic components are gone in a fossil, but there was enough in this femur to light up when we used a staining technique,” says Sarah Werning, Ph.D., assistant professor of anatomy at DMU and one of the researchers. “It’s exciting to know we can apply these techniques to fossils as well as living bone.”

Medullary bone is found only in female birds, and then only during the period before or during egg-laying as a “calcium reserve” for the eggshells. It is chemically distinct from other bone types, like the dense cortical bone that makes up the outer portion of our bones or the spongy cancellous bone found inside them. This is because medullary bone has to be laid down and mobilized quickly in order for birds to shell their eggs.

“Because medullary bone is present only when eggs are about to be laid, being able to confirm it with these histochemical stains essentially amounts to a chemical ‘pregnancy test’ for T. rex,” Werning says.

Theropod dinosaurs, the broader dinosaurian group that includes modern birds and other toothy relatives of T. rex, also laid eggs in order to reproduce, and paleontologists have hypothesized that they may have had medullary bone as well.

In 2005, Mary Schweitzer, an NC State paleontologist with a joint appointment at the NC Museum of Natural Sciences, found what she believed to be medullary bone in the femur of a 68 million-year-old T. rex fossil. She and Werning are among the authors of a paper describing the research, “Chemistry supports the identification of gender-specific reproductive tissue in Tyrannosaurus rex,” published in March in Nature online.

“All the evidence we had at the time pointed to this tissue being medullary bone,” Schweitzer says, “but there are some bone diseases that occur in birds, like osteopetrosis, that can mimic the appearance of medullary bone under the microscope. So to be sure we needed to do chemical analysis of the tissue.”

Medullary bone contains keratan sulfate, a substance not present in other bone types, but it was previously thought that none of the original chemistry of dinosaur bone would survive millions of years. However, Schweitzer and her colleagues conducted many different tests to detect keratan sulfate in the T. rex sample. They compared their results to the same tests performed on known medullary tissue from ostrich and chicken bones. To rule out the possibility of disease, they also examined pathological bones from chickens that Werning had been studying with similar techniques. Their findings confirmed that the tissue from the T. rex was medullary bone.

“This analysis allows us to determine the gender of this fossil, and gives us a window into the evolution of egg laying in modern birds,” Schweitzer says, although she adds that the fleeting nature of medullary bone means that finding more of it in the fossil record may be difficult.

Jeff Gray, Ph.D., vice president for research at DMU, praises both the research findings and the process that led to them.

“Finding medullary bone in Tyrannosaurus rex is a fascinating discovery, and it represents a great collaboration among several institutions,” he says. “The research demonstrates an ingenious approach to determine the sex of an extinct species, and it is an excellent example of using modern biomedical techniques to learn how ancient species lived on earth.”

Werning plans to use some of these same techniques in future studies of modern and fossil bone in her DMU lab.

“When I was a kid, vertebrate paleontology was totally a geological area of study. Now it’s also a biological science that is starting to incorporate biomedical science and techniques,” she says. “It’s great to bring in a variety of disciplines to come up with a holistic understanding of these extinct animals.”

Funding for the research was provided by the National Science Foundation and the David and Lucile Packard Foundation.

Probing the secret lives of dinosaurs

When Sarah Werning’s published research on dinosaur reproduction caught the eye of Vice magazine staff writer Mike Pearl last year, he had to ask her, “What’s up with their [insert colloquialism for male genitalia]?”

The sex lives of dinosaurs was an irresistible topic for the edgy magazine and its brother media channels, which probe all types of world affairs. While Pearl’s Q&A with Werning took a decidedly provocative tone (“I gave her a call to find out what kind of heat dinosaurs were packing,”

he writes), she welcomed the opportunity to discuss dinosaur sex and genital anatomy.

“All the science [in the article] is accurate, and it’s a good way to talk about how historical sciences are done,” she says. “You’re not going to be able to talk about parthenogenesis or hermaphrodite lizards in any normal news venue, but those are really interesting aspects of lizard biology. Mike is good at letting the science come through while maintaining a healthy level of juvenile humor.”