As in the human body, the anatomy department at DMU has … a lot of MOVING PARTS

Anatomy faculty at DMU have a significant teaching load, given they teach courses taken by all students in DMU’s four clinical programs and the master of science degree program in anatomy. Some faculty members have contributed to textbooks; Professor Maria Patestas, Ph.D., has co-authored the textbook on neuroanatomy. The department’s newest member, Amy Beresheim, Ph.D., anatomy lab specialist, supports the teaching load, community programs and anatomy teaching assistants, while academic assistant Linda Jensen supports everyone in the department.

Members of the anatomy department conduct research on a variety of anatomical topics. They and their students are big on community outreach, hosting high school and undergraduate students for learning sessions on campus and taking human organs to middle and high schools in central Iowa.

“The department is really great because there’s such diversity in our interests, yet we have areas that cross over so we can collaborate,” says Associate Professor Julie Meachen, Ph.D. “We’re all very outspoken, but Dr. Matz is good at leading this band of cats.”

That’s Donald Matz, anatomy department chair, who has been a member of the DMU faculty since 1995.

“The one word that comes to mind about the anatomy department over the years is ‘evolution,’ he says. “This department continues its commitment to a strong teaching effort in all the colleges while evolving, the past several years, into a competitive research entity. It is truly an honor working with and watching the department’s faculty and staff thrive professionally.”

In all the anatomy faculty do, whether it’s teaching, extracting fossils on paleontological digs or analyzing skeletal remains at a potential crime scene, their love of their field is as plain as the nose on your face.

“A lot of people think anatomy is a dead subject, no pun intended,” says Assistant Professor Lauren Butaric, Ph.D. “But there’s so much to learn about the variations in anatomy, how they happen and why it matters. There’s more to learn about the impact of lifestyles and environments on human anatomy. You will never find a human cadaver that is a textbook case.”

Crazy about carnivores

Julie Meachen’s unabashed fondness of carnivores is evident in her research, in the fact she’s a go-to source for journalists reporting on these meat-eaters and even the coyote painting that’s her computer’s screen-saver.

“I’ve just always liked carnivores. They’re so good at what they do,” she says.

Meachen, Ph.D., and Rachel Dunn, Ph.D., both associate professors of anatomy, were co-lead authors of “Locomotor correlates of the scapholunar of living and extinct carnivorans,” published in the Journal of Morphology, based on their analysis of 3D scans of five extinct animals extracted from the La Brea Tar Pits in California and Natural Trap Cave at the base of the Bighorn Mountains in Wyoming. Other authors of the article were Natalie Mironov, D.O.’20, and Joshua Lemert, D.O.’22, M.S.A.’22. It’s one of several published works by Meachen, Dunn and research colleagues from around the world that examine the effect of ecology, habitat and climate change on species evolution, adaptation and immigration.

In 2014, Meachen secured the first National Science Foundation grant awarded to a DMU faculty member to support her research in Natural Trap Cave, an 85-foot-deep sinkhole that trapped prehistoric animals during the Pleistocene Epoch – commonly referred to as the Ice Age – and amazingly preserved their fossils in its cool and clammy cavern. She also has several papers in review or revision, including on cheetahs and dire wolves. And last year, Canadian paleontologist Grant Zazula invited her to join a team of scientists studying an entirely preserved mummified Ice Age wolf pup, which still has skin and hair.

“When Grant sent me the pictures and asked me to participate in the research, I was really, really excited. I was sort of beside myself,” she told a reporter at the time. “We want to do an ancient DNA test to see who it’s related to and look wat its microbiome to see if there are gut bacteria still there.”

Different angles on examining life

Sarah Werning, Ph.D., focuses her research on the evolution of growth, metabolism and life history of vertebrates, using the evolution of bone tissue as a proxy. One of her goals is to reconstruct the physiology and life history of living and extinct species.

“I explore the processes of life, the processes of decay and what remains preserved,” she says.

An assistant professor of anatomy, Werning observed those processes in a different context as a faculty member accompanying DMU students on a global health service trip to rural Kentucky over spring break in 2018 and 2019. One of the two clinics where they saw patients is in Beattyville, one of the nation’s poorest communities in an area lacking jobs and suffering from the opioid epidemic. According to the 2013 U.S. Census Bureau, the median household income in the town, $14,871, is $38,000 less than the U.S. average.

“If you didn’t grow up in that environment, it’s easy to forget that we have aspects of the third world in our own country,” she says.

During the trip, Werning helped students get comfortable asking questions of people in the clinics and during home visits with local community health staff. She also managed logistics and provided transportation.

“I run field crews for paleontology digs, so that’s a skill I have,” she says.

Among her other projects is digitizing a collection of microscope slides found at Creighton University approximately 15 years ago. In 1909, J.S. Foote, M.D., professor of pathology at Creighton, undertook a study of cross-sections of the femurs of 600 animals, including humans, other mammals, amphibians, reptiles and birds of various ages, eras and parts of the world. Like Werning, he wanted to analyze and understand the significance of variations in bone structure. Because microscopes weren’t able to photograph slides at the time, he hand-drew them. A Contribution to the Comparative Histology of the Femur includes 467 drawings, but Foote’s collection numbers more than 1,500 slides.

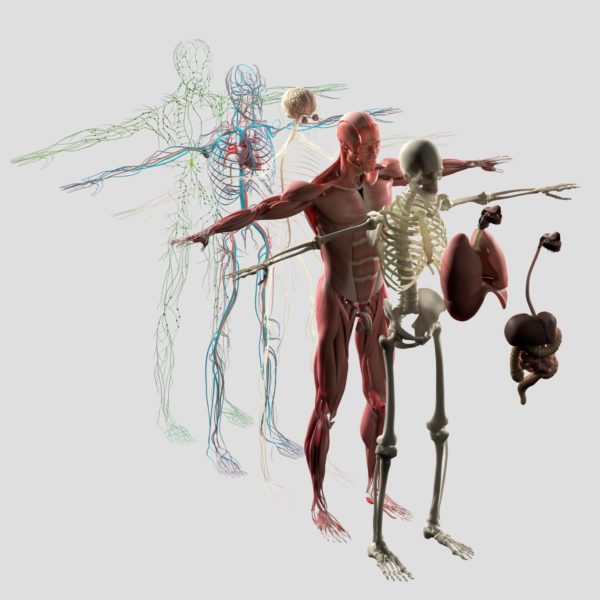

The study of anatomy began as early as 1600 B.C., but there’s still so much to learn from and about the body, from the evolution of organisms to the impact of climate change on species adaption.

“He wound up creating a really interesting, thorough sample set with a modern understanding of relationships. It was a major contribution but then it kind of went by the wayside,” says Werning, who used some of Foote’s slides in her dissertation for her Ph.D. in integrative biology at the University of California-Berkeley.

Deconstructing the “fingerprint of the skull”

Lauren Butaric, Ph.D., has spent a fair amount of time hunting through dusty bins of skulls at museums and universities, searching for ones that aren’t broken so she can take CT scans of their nasal sinuses and use them to produce 3D models.

“Some museums have scanners in-house; others I have to lug to local hospitals to scan,” says the assistant professor of anatomy. “I had to hire a taxi cab to haul 50 skulls across Central Park. Only in New York would a taxi driver not be disturbed that he’s loading human skulls in his van.”

The 2019 recipient of the DMU Faculty Organization’s inaugural Paul E. Emmans Outstanding Faculty Teacher Award, Butaric focuses her research on craniofacial variation, particularly the internal structures of the skull and ways they vary. She compares the nasal cavity and sinuses among skulls of individuals from different geographic locations. For example, people from hot-wet climates tend to have wide nasal cavities; those of people from cold-dry climates are tall and narrow to warm and humidify inhaled air to protect the lungs.

There’s so much more to learn about the structure and development of the nasal cavities, however. “We don’t know that much about how the shape of the nasal cavity is affected by climate, temperature, dust and pollen, or about the variation in those structures among males and females in different environments,” she says.

Nor has much research been done on the facial/nasal structures of children. Butaric is working with an anatomy professor at the University of North Texas to create digital models of children’s air spaces; she’s working also with an aerospace engineer there in using airflow dynamics to understand how air flows through models of differently shaped nasal passages.

English physician William Harvey, the first to recognize the full circulation of blood in the human body, said, “I learn anatomy not from books but from dissections, not from the tenets of philosophers but from the fabric of nature.”

In addition, Butaric and Heather Garvin, Ph.D., associate professor of anatomy, obtained an internal DMU research grant related to assessing error rates in using the frontal sinuses of the skull to identify deceased individuals, given the high level of precision required in a court of law.

“The frontal sinuses are so variable among people. They’re the fingerprint of the skull,” Butaric says.

Understanding more about craniofacial structure, variation and the purposes of that variation is important to life and health in a changing environment, she says.

“Coming from an anthropological background, I look at how and why our physical structures vary,” she says. “Now that I’m at a medical school, I can also ask, ‘Why should we care?’”

Solving skeletal mysteries

Heather Garvin, Ph.D., D-ABFA, knows: The dead do tell tales.

The associate professor of anatomy is among approximately 90 board-certified forensic anthropologists in the nation and the only one in Iowa. She assists the state medical examiner’s office in scene recoveries, skeletal identifications, interpretation of skeletal trauma and testifying in court as necessary.

“Forensic anthropologists are experts in the human skeleton. Medical examiners call us in any time an analysis of skeletal remains could provide information about the circumstances of death,” she says. “That can be anything from skeletonized remains found in the woods to child abuse cases to airplane crashes.”

In 2014, she joined an investigation on a much older skeletal mystery – the identification of a new human ancestor, Homo naledi, discovered in a remote chamber of the Rising Star cave system near Johannesburg, South Africa. The hominin species, thought to have survived until between 226,000 and 335,000 years ago, had a tiny brain and humanlike features. As part of a team of scientists from around the globe, Garvin is responsible for estimating the “new species’ body and brain size. Discover Magazine named the finding the number-two top science story of 2015, second only to a NASA space probe’s photos of the surface of Pluto.

Garvin was among the authors of ““Endocast morphology of Homo naledi from the Dinaledi Chamber, South Africa,” published last year in the journal PNAS.

“It’s a hot topic of debate and was all over the international press, as some believe this hominin species that had a brain one-third the size of ours was intentionally depositing their dead in this cave system,” she notes.

Garvin has two ongoing federally-funded research grants through the National Institute of Justice. A $186,605 grant is allowing her, Rachel Dunn, Ph.D., associate professor of anatomy, and a collaborator at the Smithsonian Institution to create “OSTEOID,” a new online resource for criminal investigators, medical examiners and others to identify the species of skeletal remains. Garvin also has a $510,574 grant, with collaborators at the University of Nevada-Reno, to use postmortem CT scans of juveniles to create new standards for sex and age estimation from skeletal remains. DMU students are working on both projects.

“I came to DMU because teaching is emphasized here,” Garvin says, “but the University also supports faculty research.”

Putting together puzzles of paleontology, teaching

Associate Professor Rachel Dunn, Ph.D., has excavated and analyzed ancient skeletal specimens in several states, Egypt and India. This past summer alone, she hauled 500 pounds of matrix from a dig at Sand Wash Basin in northwestern Colorado, from which she extracted 14 pounds of material to comb through. Her mission: to uncover how patterns in mammalian morphology and diversity reflect changing climates during the Eocene Epoch, 55 million to 34 million years ago, a time in which most modern mammal groups evolved.

“I’m interested in how we can predict the behavior of animals from their hard tissue, the bones, and how the environment changed them,” she says.

In 2015, Dunn was on a team of researchers that found in Gujarat, India, 25 exquisitely preserved bones from the most primitive primate yet discovered in terms of evolutionary development, a tree-dwelling creature that could sit on the palm of your hand. She was lead author of a paper on the discovery published that year in the Journal of Human Evolution. It was named number 65 in Discover Magazine’s top science 100 stories of 2016.

“These fossils give us the best picture of what that very first primate looked like,” she told the magazine.

Fascinated by natural history since preschool, Dunn had her sights set on a career as an anthropologist/paleontologist. When she was a graduate student at Washington University, her adviser encouraged her to hone a more “marketable skill” – teaching.

“As I taught, I began to find my own joy in the process of teaching,” she says. She’s very good at it: In 2018, she received the College of Osteopathic Medicine Dean’s Award for Outstanding Teaching and the DMU Faculty Organization’s Outstanding Teaching Award; in 2019, the College of Podiatric Medicine and Surgery Student Government Association recognized her for outstanding teaching in the basic sciences. She consistently earns high student evaluations for her teaching clarity, organization, enthusiasm and ability to incorporate fun in her lecture style.

“I love puzzles. That’s why I love paleontology,” she says. “Teaching is like that, too. I want to convey information, so I work on how to put facts together in an intelligible manner that expresses their relevance for the students.”

A behind-the-scenes hero

Because of its many courses and labs, research endeavors and community outreach that DMU’s anatomy department manages, every day is different for Kathleen Bitterman, the department’s lone research assistant. One week she may be preparing tissues of canine brains for the comparative anatomy investigations of Associate Professor Muhammad Spocter, Ph.D.; the next, curating the 4,000-plus specimens of Ice Age-era mammals, reptiles and birds excavated by Associate Professor Julie Meachen, Ph.D., and others from Wyoming’s Natural Trap Cave.

Yet another week she might be researching, purchasing and setting up new lab equipment or creating 3D anatomical models using laser scanning technology and other software.

“Every day changes. I need to be nimble and creative depending on what our researchers’ projects are,” she says. “I love anatomy and the research is fascinating, so it’s really a blast.”

Bitterman plays a role in teaching, too, on campus and in community outreach. “The students I’ve encountered through our programs love science, and I want to open new doors for them,” she says. “When we explore the comparative anatomy of the brain or skeleton, you can see the light bulbs come on.”

She’s also helping develop a collection of human brain stem slides to be used in the new edition of the neuroanatomy dissection guide and online laboratory. She uses sectioning tools and different kinds of tissue stains to produce the slides.

“Each stain we use has a specific target. In the brain stem project, we’ll visualize the white matter and the gray matter using different recipes and techniques depending on the specimens and goals,” she explains. “I love helping solve the mysteries of anatomy and using new technology to answer scientific questions. I have a dream job.”

Thanking the silent teachers

Some of the most important people in an academic anatomy department aren’t even alive. People who choose to donate their bodies to DMU and other medical institutions are clinical students’ silent but crucial teachers.

“If an average of 10 medical students learn from one body donor, that donor and the students will have impacted more than 1.1 million patients in a 30-year career,” says Edward Christopherson, a licensed embalmer and former funeral director who’s served as DMU’s anatomical coordinator since 2014.

Courses and labs for clinical students and those in the master of science in anatomy program require 55 body donors per year. Every year, 120-125 people register to donate to the program, and approximately 2,900 individuals are currently registered.

“Body donation is becoming more prevalent. People want their bodies to be used for educational purposes,” Christopherson says.

Arrangements are made for donors’ remains to be returned to the families, sent to a funeral home for memorial services or interred at Chapel Hill Gardens in Des Moines. If a donor is a veteran, his or her remains can be interred, at no cost to the donors or their families, at the Iowa Veterans Cemetery in Van Meter.

“I think that’s very important for veterans as their final dignified service,” Christopherson says. “I arrange for the chaplain, the military funeral honors and students to attend the burial with the permission of the family.”

He and the department work to ensure students understand and appreciate the great gift body donors make. Beginning in 2018, DMU’s Body Donor Memorial Service offered families the option of wearing a lanyard identifying their donor’s family, a signal to students they want to talk about their loved one during the post-service reception.

“It’s meaningful when we can connect families, if they want, with our students,” he says. “It wraps up everything for the students. They want to thank the families, and it lets them learn about the donor in life.”