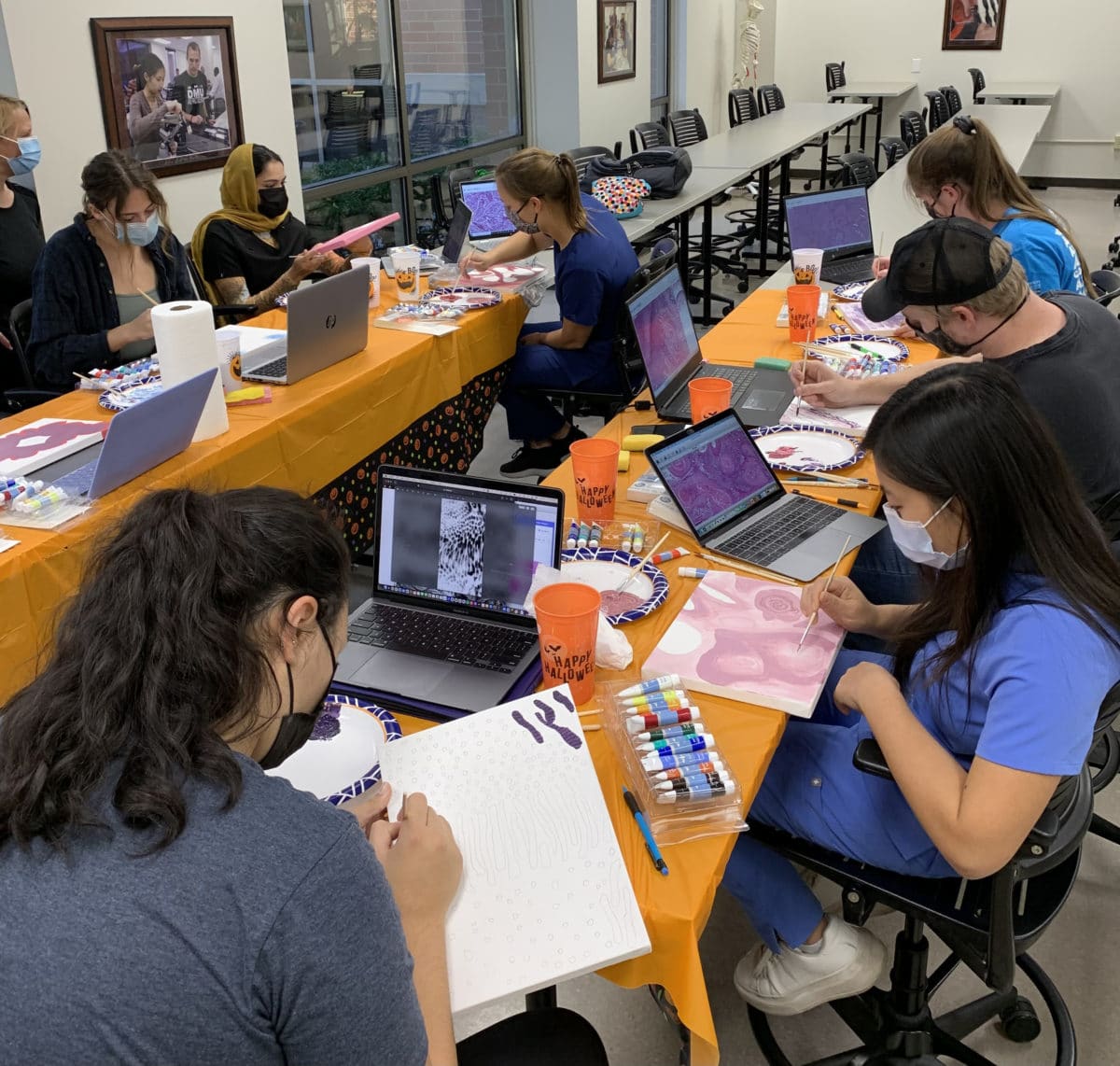

On a recent October evening, several students gathered in the Bako Laboratory in the Student Education Center on the DMU campus – not to discuss physiology or anatomy, but instead to paint colorful depictions of medical diagnoses. The event was one of several opportunities sponsored this month by the Medical Humanities Society (MHS), a student organization that invites students and others to explore the arts and social sciences as they relate to medicine, emphasizing how an understanding of the human condition can inform medical practice.

“What is great about MHS is the huge breadth of our mission. Overall, I think of it as somewhat of a respite from the hard sciences we focus on for most of our day and a way to focus on personal growth and development outside of the classroom,” says Lauren Young, MHS president and a second-year osteopathic medicine student.

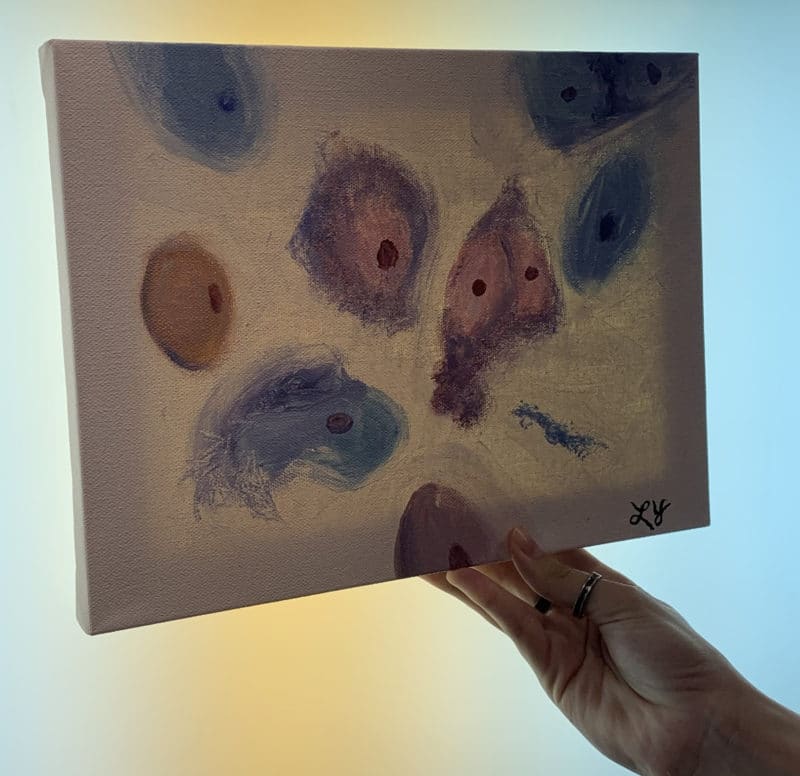

Mikayla Brockmeyer, MHS treasurer and a second-year osteopathic medicine student, got the inspiration for the “Paint Your Diagnosis” event in 2018, when she was a student in DMU’s master of science in biomedical sciences (M.S.B.S.) program. At the time she was doing research in the pathology lab of Yujiang Fang, M.D., Ph.D., an academic pathologist and associate professor of microbiology and immunology. She decided to produce a watercolor painting of a histology slide and “deconstruct the meaning behind it.”

“The guiding principle and thought behind this [painting] exercise is that it is cathartic and emotionally healing for the soul to visualize our internal, deepest pathologies, or typically what are thought of as ‘wrong with us,’” she says. “The act of painting our diagnoses, on canvas, cell by cell, brings us more in tune with our internal perception of self and what it is like to have this disease, or diagnosis.”

For the event, Sarah Werning, Ph.D., associate professor of anatomy, provided a slide set and shared her expertise. Some students painted diagnoses they’d had, while others painted diagnoses of family or friends. Students shared perspectives from their paintings if they were comfortable in doing so.

“By understanding our cellular components and the nature of both dysfunction and healing, presenting in one body, we were able to have a meaningful, connective experience,” Mikayla says. “Ultimately, this event required all attendees to expose some vulnerabilities, but the outcomes were beautiful works of art and a deepened sense of connection with the diagnosis of their choosing.”

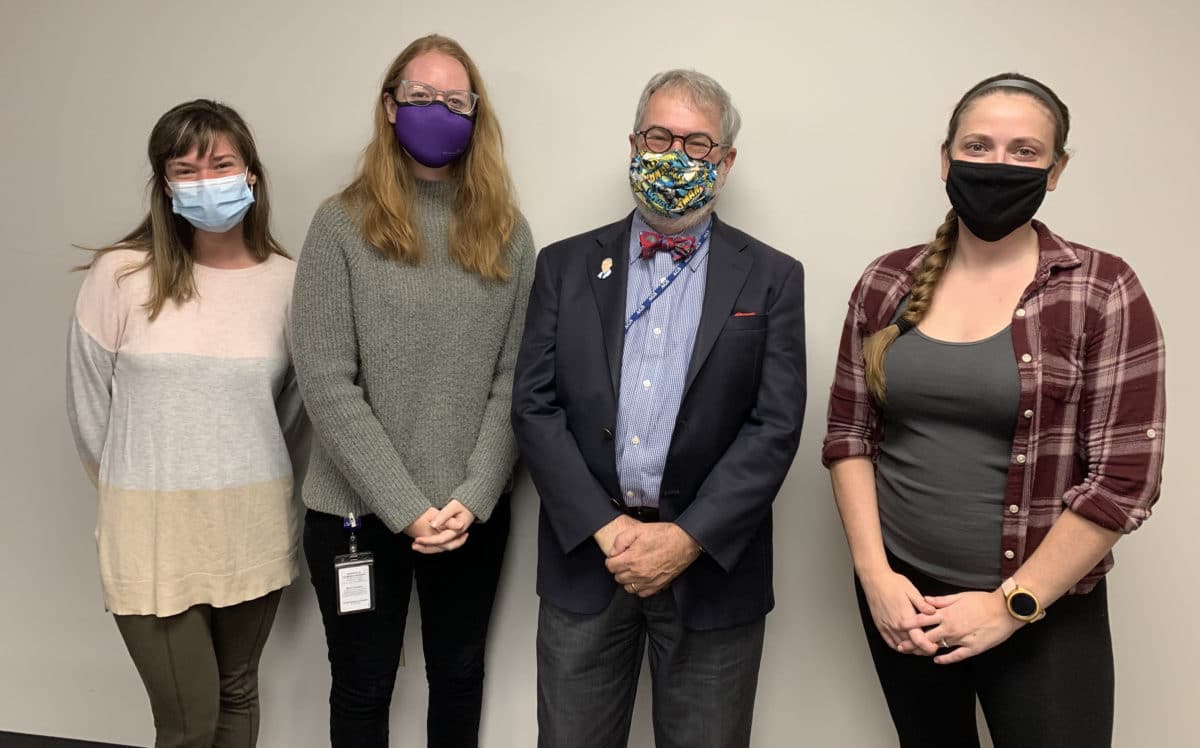

At another recent MHS event, Paul Volker, M.D., FAAFP, assistant professor of osteopathic clinical medicine, presented a free-wheeling “humanities mash-up” that evoked applause, laughter and a few gasps. He began with readings from books by physician authors, including Mortal Lessons: Notes on the Art of Surgery by the late Richard Selzer, M.D. He read some 55-word medical essays used by several physicians as an outlet given the emotionally draining aspects of medical practice. He also showed a 1954 video depicting a staphylococcus outbreak; displayed 1950s print ads promoting the health benefits of smoking, which would have been laughable if they hadn’t been so flagrantly false; and read descriptions of surgical procedures done before the development of anesthesia from Lindsey Fitzharris’ book, The Butchering Art: Joseph Lister’s Quest to Transform the Grisly World of Victorian Medicine.

“In medical school, it’s hard to find time to read for fun, and if you do take the time, I think you should read something not related to medicine,” Dr. Volker told the audience. “But if you’re interested in the history of medicine, there are lots of good books out there.”

He concluded with wellness tips for students, including getting some sleep, reading for fun some of the time, enjoying the arts and outdoors and nurturing relationships. Other Medical Humanities Society events – including a Saturday tour of Des Moines’ Sculpture Park and its November book club pick, S.A. Cosby’s novel Razorblade Tears – are designed to help students further tap the humanities for insights, balance and enjoyment.

“We try to have a broad definition of the humanities and include a little of everything such as literature, creative writing, art, music, religion, ethics, etc. Not only are these topics that students are interested in, but I think they are also things that will shape us into better providers and better humans,” Lauren Young says. “Our events allow students to flex the creative muscles they may not normally get a chance to and meet like-minded students and faculty, which is really great in the past months which have been isolating for many.”