Oh, ticks.

For some reason, they make your skin crawl more than their more ubiquitous blood-sucking brethren, the mosquito. This is odd because the mosquito contributes to far more overall morbidity and mortality worldwide, but there’s just something a little more unsettling about finding a tick on you. There’s just something about a little arachnid (they’re members of the arachnid family) crawling underneath clothing and burrowing their way into aahHALLAWEWWWW! *Shivers uncomfortably*

I don’t even want to think about it! I want to prevent it!

Because (and this is a wonderful aphorism I collaborated with Ben Franklin on) an ounce of prevention is worth several trillion dollars of cure. By the way, that applies across the board in medicine.

Anyway, first, let’s talk about some of the various tick-borne diseases out there, along with some signs, symptoms and treatments. Then we’ll go into some basic steps that can help you avoid ticks making a meal out of you.

Types of Tick-Borne Diseases

The first tick-borne disease that everybody understandably thinks about is Lyme disease. Lyme disease is a relatively new disease, first recognized in Lyme, Connecticut, in the 1970s. It was misidentified as something else (that historical note will be relevant in a few paragraphs). Lyme disease is caused by the bacteria Borrelia burgdorferi and Borrelia mayonii in North America. In other parts of the world, different Borrelia species can cause Lyme disease. You’re probably reading this in North America, so let’s stick there.

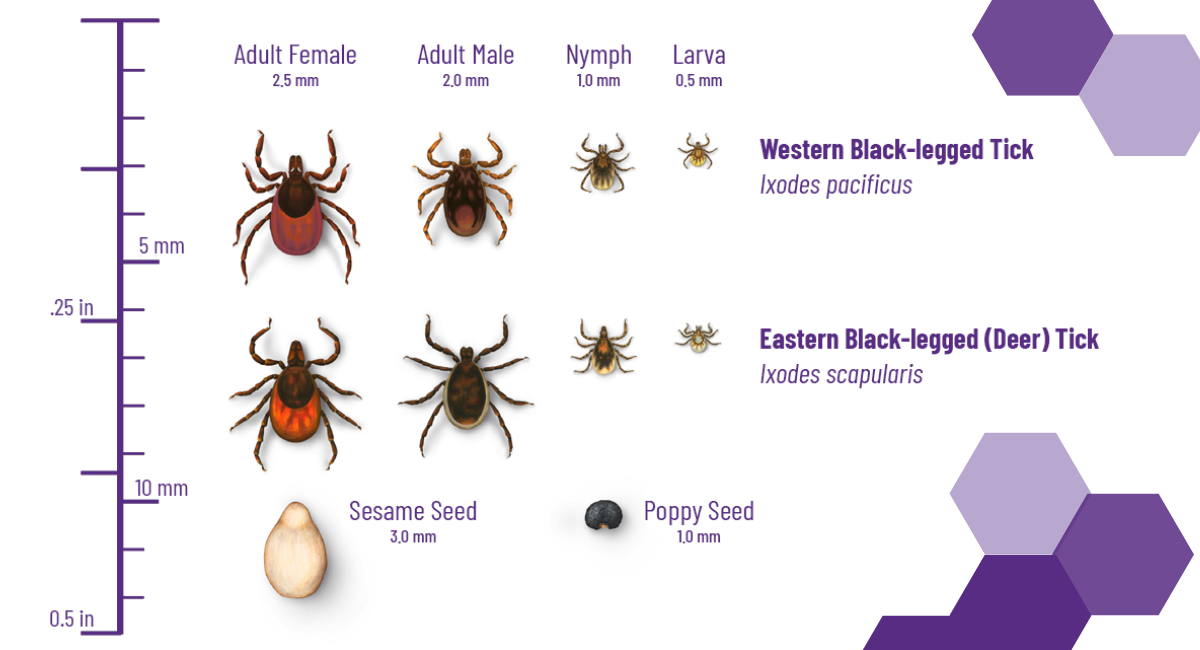

The main tick that transmits Lyme disease is the deer tick, a.k.a. the black-legged tick (Ixodes scapularis) and the western black-legged tick (Ixodes pacificus). Unfortunately, those two species can be found across the United States. Ixodes scapularis is particularly prevalent in the Northeastern United States and the Great Lakes Region. It’s also prevalent in Florida but can be found in all states east of the Mississippi and bordering the Mississippi — certainly Minnesota, Iowa, Missouri, Arkansas and Louisiana. Ixodes pacificus is primarily concentrated on the Pacific coast — California, Oregon and Washington — though there have been cases reported east of that.

One important thing to note is that Ixodes scapularis and pacificus go through the same life cycle stages, and this is relevant too. These ticks go from the larva to nymph to adult stage over two years and need a blood meal each time to switch stages.

It’s estimated that most cases of Lyme disease occur when the tick is in the larva stage, which is obnoxious because the tick is quite a bit smaller and harder to see. If you pick up a standard U.S. dime and flip it over, a larval deer tick is about the size of the “D” in the word “dime” on the back of the coin. Aside from them being hard to see because of their size, when the tick is in the nymphal stage, its bite is painless and often goes unnoticed. These ticks usually need to be burrowed into somebody for about 36 hours for Lyme disease to be passed to the host (you would be the host).

Signs and Symptoms

If the bacteria is passed to a human, the first thing usually noticed is the characteristic bull’s-eye rash that most everybody talks about. This rash shows up in about 80% of cases and typically shows up one to two weeks after the bite happened. The rub is that most people don’t realize that they got bit. The classic bull’s-eye pattern is sometimes observed, but if an expanding rash seems circular, it doesn’t matter if that bull’s-eye pattern isn’t there. Usually, some other symptoms accompany this — fatigue, anorexia, headache, neck stiffness, muscle aches, joint pain, lymph nodes that get large and inflamed and fever.

Treatment

If somebody comes in with those symptoms, AND they’ve got the rash, AND they’ve been in an area where the Ixodes species usually live, we’re done. The patient gets treated for Lyme disease. Fortunately, this is a bacterial disease, and right now, plenty of our antibiotics still work. Doxycycline and amoxicillin still work quite nicely, which is another reason for us to practice judicious antibiotic usage at other times. Overusing antibiotics for things like viral respiratory infections (common colds) lessens their effectiveness when we really need them. Anyway, we’d still run the lab tests just to be sure, but that’s not necessary if the rash, the symptoms and the location and exposure are correct.

Remember a few paragraphs up when I said that Lyme disease was first misidentified?

Back in 1975, there was a cluster of kids who all had the same rash and the same muscle aches. It was misidentified as juvenile rheumatoid arthritis. Well, that’s relevant today because Lyme disease has become the Great Imitator. Lyme disease can have all sorts of odd manifestations. When the bacteria disseminates throughout the body, it can cause a breathtaking array of symptoms, including nerve, heart, eye, and chronic muscle and joint problems. Before people figured out antibiotics could sort this out, chronic nerve problems came along with Lyme disease. Missing the diagnosis early can lead to chronic problems later, so if you notice an expanding rash or have been having nagging joint and muscle pains AND tick exposure, you should see a doctor immediately.

Rocky Mountain Fever

Rocky Mountain wood tick

Unfortunately, Lyme disease isn’t the only disease you can get from ticks. You might have noticed that the black-legged and the western black-legged tick spares quite a bit of the Rocky Mountain Range. Sadly, there’s also a disease called Rocky Mountain spotted fever caused by the bacteria Rickettsia rickettsii, which takes its name from the Rocky Mountain wood tick that likes to spread it. That tick lives in the Rocky Mountain region. The bacteria that causes Rocky Mountain spotted fever can also be spread by the dog tick, which is distributed across the eastern United States.

Rocky Mountain spotted fever happens much less frequently than Lyme disease, but it can be just as problematic. Early symptoms can include fever, nausea, vomiting, headaches and muscle pain. The symptoms aren’t dissimilar to Lyme disease, and this continues into the later stages. Honestly, the symptoms of Rocky Mountain spotted fever are like other ailments, making identification tough. Exposure to ticks will be the biggest piece of a patient’s history that would tease this out.

There is a rash that can show up with Rocky Mountain spotted fever. It is (not surprisingly) a “spotty” looking rash. Curiously, it starts on the hands and other extremities and then moves inward toward the trunk. The rash usually takes two to five days to emerge and is quite subtle at first. It may take a few days for the rash to become prominently red and spotted, and sometimes that may not happen at all. Rocky Mountain spotted fever can cause disabilities that can be permanent, including sensory problems like blindness or deafness, cognitive deficits and sometimes even gangrene requiring amputation.

There are a few other diseases that can be tick-borne as well. Pull out your dictionary! These are anaplasmosis, babesiosis and ehrlichiosis. Some of these diseases can come along with other diseases. It’s common for people to have co-infections with Lyme disease and anaplasmosis or babesiosis at the same time. Going into the details of those conditions would be a little beyond the scope of this article, so let’s try to sum this up.

Did you have significant tick exposure? Were you walking in tall grass? In the forest? In tall weeds? Camping? Out in nature? Yes? Now are you having unusual headaches, muscle aches, fever, chills, stomachaches, nausea, significant fatigue and/or inflamed lymph nodes? Or do you have a weird-looking rash?

In other words … were you exposed to ticks and are you now symptomatic? See a doctor!

Okay, that’s what to look out for and worry about if you get bitten by a tick. As we already discussed, it’s quite a bit better to never get bit by a tick in the first place, right?

Right!

So, let’s finish with that.

Prevention

There are a few things that people have tried that theoretically might work but haven’t exactly been shown to be practically effective. The first is tick checks — like the country music song by Brad Paisley that came out in 2007. It’s just what you think — you’re just checking a partner head to toe for ticks. While this might be romantic on country music radio stations, unfortunately, no evidence suggests it prevents tick bites or Lyme disease. Remember that the tick spreading Lyme disease is usually in the larval stage, so tick checks tend to miss the difficult-to-spot larval deer tick. The thing is, a tick-check is *in no way* harmful, so by all means, go ahead and make Brad Paisley proud. Just don’t rely on it as the end-all, be-all.

People have also theorized that throwing your clothes in the dryer when you get home will help. This works again in theory. A dryer with dry clothes on high will kill ticks in five minutes, but interestingly, it took almost 50 minutes to kill ticks if some wet clothes or towels were being dried with the tick-infested clothing. The point is that relying on a dryer to kill ticks isn’t reliable enough.

What’s your best bet to prevent tick bites?

Long-legged and long-sleeved clothing that’s been treated with permethrin. Any pants and shirt will do. And you can easily treat it yourself with over-the-counter permethrin spray. A company called Sawyer makes it and it’s readily available online. Permethrin spray is perfectly safe for humans (I mean, don’t drink it or anything), but on your clothes, no problem. It’s quite fatal to ticks and other nasty beasties out there wanting to make a meal of you (well, nasty beasties that are insects). In addition to treating your clothes with permethrin, you can apply a DEET repellant on your skin. The treated clothing and repellant on your skin are going to be your best shot at preventing tick bites.

It is also worth mentioning that while tick-borne illnesses are certainly possible across the country (except for Hawai’i), certain parts of the country are more prone to Lyme disease specifically. That would be the Northeastern United States. So, if you’re REEEALLY afraid of ticks but you REEEEAALLY want to go hiking, go West, young person.

I hope this will let you know what to look for in terms of symptoms, what can be done if you do get sick and most of all, how to prevent it from happening in the first place!

The expert family medicine providers at the Des Moines University Clinic can help you and your loved ones stay healthy this summer and beyond. For more information or to make an appointment, visit the DMU Clinic website or call 515-271-1710.